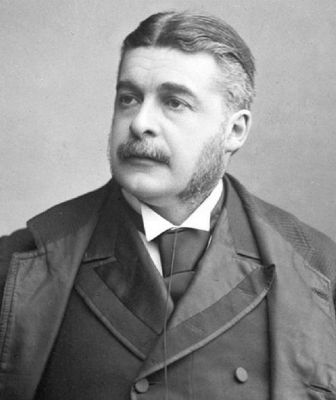

Arthur Sullivan

(1842-1900)

Sir Arthur Seymour Sullivan was an English composer, most widely recognized for his 14 operatic collaborations with dramatist W.S. Gilbert.

Sir Arthur Seymour Sullivan was an English composer, most widely recognized for his 14 operatic collaborations with dramatist W.S. Gilbert.

Born to a musical family in London, Sullivan began composing from an early age—he wrote his first anthem at age eight. The son of a military bandmaster, he was awarded the first Mendelssohn Scholarship by the Royal Academy of Music in 1856, when he was 14. The scholarship allowed him to study at the Academy for a year and then attend the Leipzig Conservatoire. While in Germany, one of his principal teachers was Carl Reinecke. Sullivan was trained in Mendelssohn’s ideas and techniques, but was also exposed to a variety of musical styles, including the writings of Bach, Schubert, Verdi, and Wagner. His graduation piece was an immediate success, and he began writing fervently. Though he originally began composing serious works, he continued to write light works like hymns and ballads as well. From 1861-1872, he supplemented his income by working as both a church organist and music teacher.

Sullivan’s first opera was composed in 1866, the one-act comic work Cox and Box. The combination of his musical talent and natural charisma and charm garnered him many friends in elite musical and social circles. Although Sullivan never married, he had several serious love affairs. The first was Rachel Scott Russell, daughter of engineer John Scott Russell. Rachel’s parents did not approve of a possible union with a young composer with uncertain financial stability, but the two continued to see each other. In 1868, Sullivan started a simultaneous secret affair with Rachel’s sister Louise, but both relationships ended by early 1869.

Sullivan's longest love affair was with the American socialite Fanny Ronalds, a woman three years his senior, who had two children. He met her in Paris around 1867, and the affair began soon after she moved to London permanently in 1871. Ronalds was separated from her American husband, but they never divorced. She was a constant companion up to the time of Sullivan's death. In 1896, the 54-year-old Sullivan proposed marriage to the 22-year-old Violet Beddington, but she refused him.

Sullivan loved to spend time in France (both in Paris and the south of France), where his friends ranged from European royalty and socialites to composer Claude Debussy, and where he could often indulge his passion for gambling. He was a very social person and enjoyed entertaining, hosting private dinners and events featuring famous singers and well-known actors. Despite his bachelorhood, he remained very close with his family. His brother Fred died at the age of 39 in 1877, leaving his pregnant wife, Charlotte, with seven children under the age of 14. After Fred's death, Arthur visited the family often, became guardian to all of the children, and financially supported the entire family, an act he would continue until his own death.

His first joint work with W.S. Gilbert, Thespis, was written in 1871. The duo went their separate ways after the premiere, and Sullivan continued to write a variety of music. In addition to the extensive composition he was doing, he also received several conducting and academic appointments. In 1875, Gilbert and Sullivan were reunited at the request of producer Richard D’Oyly Carte, and the result was Trial by Jury, followed by the international sensations H.M.S. Pinafore, The Pirates of Penzance, and Patience. Carte used his profits from the Gilbert & Sullivan partnership to build the Savoy Theatre in the West End in 1881. The remaining joint works resulting from this collaboration have become known as the “Savoy Operas”.

After Iolanthe in 1882, Sullivan had intended to take a break from writing with Gilbert, but suffered a great financial loss and eventually concluded he must continue to compose the Savoy operas. He and Gilbert signed a five-year agreement with Care, which required them to produce a new comic opera on six months’ notice. In May of 1883 Sullivan was knighted by Queen Victoria for his services rendered to the promotion of the arts and music. With this honor, many critics believed this should put an end to his career as a composer of comic opera—a musical knight should not stoop below a grand opera or oratorio. In mid-December of that same year, his sister-in-law emigrated to America with her family, but Sullivan’s oldest nephew Herbert stayed in England and became his uncle’s ward.

A dispute in 1890 over financial costs of renovations to the theater caused Gilbert to take legal action against Sullivan and Carte, and vowed to cease writing for the Savoy. Therefore, the partnership came to a bitter end. Eventually with the help of Tom Chappell, their music publisher, the two were brought back together but their relationship was never the same and the resulting two operas were far less successful.

Sullivan died at the age of 58 from heart failure following an attack of bronchitis. Although he wished to be buried with his brother and his parents in Brompton Cemetary, he was buried in St. Paul’s Cathedral at the order of the Queen. His comic opera style served as a model for the generations of musical theatre composers that followed, and his music is still frequently performed and recorded.

Sullivan’s body of works include 23 operas, 13 major orchestral works, several choral works and oratorios, 2 ballets, various sacred hymns and writings, and assorted chamber works. Apart from the Savoy operas, his legacy is most recognized in his mark left on American and British musical theatre. Trained in the classical style, contemporary music did little to interest him, and his early works used conventional formulas of the times and contained a heavy Mendelssohn influence. Throughout his compositional writings, Sullivan would retain the ability to draw on various influences without losing his own recognizable sound. He greatly preferred to write in major keys, even in his serious works. His best known contrapuntal device was the simultaneous presence of two or more distinct melodies previously heard independently. Though he wasn’t the first composer to use this technique to combine themes, it became an identifying characteristic of the Gilbert and Sullivan operas. Sullivan’s scoring, especially his woodwind orchestration, is also an identifying feature of his works. He had no inhibitions in writing for all registers of the clarinet, and had a particular fondness for solo oboe passages. He would often quote or imitate famous themes from well-known tunes, or parody the style of other famous composers.

Click below to Arthur Sullivan titles:

t7t3l0uhl8|0010C39D6D07|DetailContent|contenttext|DB7C2A7C-0DA3-4414-9944-98CC54DEC153

<